On April 3, 2025, the US Senate confirmed Dr. Mehmet Oz as the next administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). In congressional hearings preceding his confirmation, Dr. Oz testified that he will be the “new sheriff in town,” particularly with respect to Medicare Part C, also known as the Medicare Advantage program (MA Program). As the Trump administration proceeds with its stated efforts to minimize fraud, waste, and abuse in federal programs, health plans and providers involved in the MA Program should be aware of recent developments concerning False Claims Act (FCA) liability and prepare for increased enforcement activity.

Medicare Advantage Program overview

The MA Program is the largest component of Medicare, both in terms of federal dollars spent and the number of beneficiaries impacted. Under the MA Program, Medicare beneficiaries enroll in private health insurance plans that offer Medicare benefits (MA Plans). MA Plans are paid a per-person amount to provide Medicare-covered benefits to enrolled beneficiaries. CMS adjusts the payments to MA Plans based on beneficiary demographic information and health conditions. These risk adjustments are determined by an individual’s “risk score”—a number based on the predicted costs for treating a particular beneficiary based on the individual’s diagnoses. In general, a beneficiary with diagnoses that are more expensive to treat will have a higher risk score, and CMS will make a larger risk-adjusted payment to the MA Plan for that beneficiary.

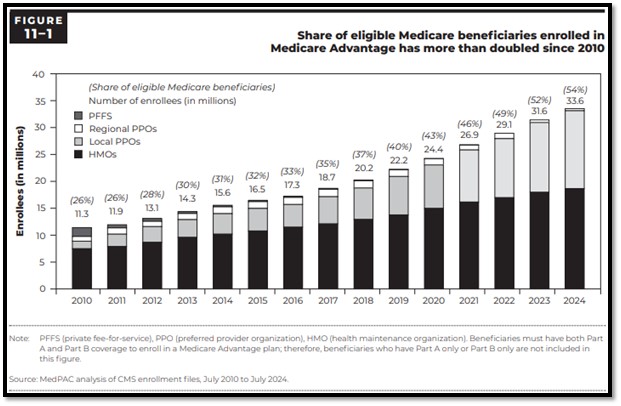

The share of eligible Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in the MA Program has more than doubled since 2010. According to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission’s (MedPAC) March 2025 Congressional Report on Medicare Payment Policy, in 2024, the MA Program enrolled about 33.6 million beneficiaries (more than half of eligible Medicare beneficiaries). 175 Medicare Advantage Organizations (MAOs) offered 5,678 plan options in 2024, and CMS paid MA Plans an estimated $494 billion (not including payments for drug coverage).

Chart review scrutiny & Poehling

On January 15, 2025, five days before President Trump’s inauguration, the Department of Justice (DOJ) released its annual report on FCA settlements and judgments for fiscal year 2024. DOJ’s fiscal year 2024 report continued the trend in recent years of highlighting enforcement activity involving the MA Program, including several ongoing actions that DOJ has actively litigated since President Trump’s first term. One such action is United States of America ex rel. Benjamin Poehling v. UnitedHealth Group, Inc., Case No. 16-cv-08697 (C.D. Cal.) (Poehling).

Poehling was initially filed as a qui tam action in 2011 by the former finance director for UnitedHealth Group, Inc. (UHG), the nation’s largest MAO. The relator alleged that UHG and several other MAOs knowingly (i) submitted or caused to be submitted false risk scores to CMS in order to improperly increase MA Program payments and (ii) retained overpayments from CMS as a result of false risk adjustment submissions.

During President Trump’s first term, DOJ filed a complaint-in-intervention in Poehling against UHG, alleging that UHG fraudulently retained $2.1 billion in overpayments by knowingly disregarding information about beneficiaries’ medical conditions, resulting in improperly inflated risk adjustment payments. In particular, DOJ contended that UHG conducted a “one-way” chart review program designed to identify diagnoses supported by medical records but not reported (which would increase risk adjustment payments), but which ignored diagnoses reported but not supported by medical records (which would decrease risk adjustment payments). Given these “one-way” chart reviews, the government alleged that UHG violated the “reverse false claims” provision of the FCA, 31 U.S.C. § 3729(a)(1)(G), which renders liable anyone who knowingly conceals or knowingly and improperly avoids an obligation to pay money to the government (such as an identified overpayment).

On March 3, 2025, after eight years of contentious post-intervention litigation, the special master assigned to the Poehling matter issued a report recommending summary judgment in favor of UHG.[1] In so recommending, the special master concluded that the government failed to present any evidence that UHG (i) submitted unsupported diagnosis codes to CMS or (ii) acted with the requisite intent with respect to any alleged overpayments. Specifically, the special master determined that the government did not meet its evidentiary burden to defeat summary judgment because it simply assumed—without reviewing any medical records, via sampling or otherwise—that if a UHG coder did not identify a diagnosis code submitted by UHG to the MA Program in the course of a chart review, then such diagnosis code was necessarily invalid. Accordingly, the special master concluded that the government failed to provide any evidence of an actual reverse false claim (i.e., overpayments to UHG based on diagnosis codes not supported by medical records).

The special master further found that summary judgment in favor of UHG was warranted because the government failed to provide any evidence that UHG engaged in any deception or knowingly or improperly avoided any obligation to return any alleged overpayments to CMS. In so finding, the special master noted that, as early as 2014, UHG disclosed the nature of its chart review program and medical record review practices to CMS, as well as the fact that its chart review program was not designed to confirm the validity of diagnosis codes submitted by doctors.

On April 2, 2025, the government asked the Poehling court to reject the special master’s report and recommendation. In support of such relief, the government argued that the special master improperly weighed evidence and improperly interpreted the FCA’s “reverse false claims” provision to require proof of an affirmative act of deception. The Poehling court has set a June 5, 2025, hearing on the government’s motion.

Notwithstanding the Poehling court’s ultimate decision on the special master’s report and recommendation, MA Program plans and providers should be cautious about viewing the report as a blanket endorsement of chart review programs generally. In December 2019, during President Trump’s first term, the US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (HHS-OIG) published a report outlining its concerns associated with the billions in estimated MA Payments stemming exclusively from chart reviews. There have also been several large FCA settlements in recent years relating to MA Program chart reviews, many of which stemmed from qui tam complaints and resulted in five-year corporate integrity agreements. Further, in October 2024, HHS-OIG published a supplemental report identifying chart reviews and health risk assessments (i.e., assessments conducted by healthcare professionals to collect information from enrollees about their health conditions) as particularly vulnerable to misuse by MA Plans, finding that such reviews and assessments caused an estimated $7.5 billion annually in MA risk-adjusted payments. Accordingly, while the special master’s report and recommendation in Poehling is a favorable development for UHG, MA Program plans and providers (including those deploying novel artificial intelligence tools to support and defend MA Program coding) should expect that the government will continue to scrutinize chart review programs and that the parameters of chart reviews will continue to serve as bases for FCA actions.

Improper marketing arrangements

Apart from chart review scrutiny, individuals and entities involved in the MA Program should anticipate increased scrutiny of marketing arrangements—including in connection with MA Program Special Needs Plans (SNPs), which offer benefit packages tailored to specific populations (such as beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, are institutionalized, or have certain chronic conditions). Parameters governing MA Program marketing are currently set forth in both regulations and guidance.[2] Effective as of plan years 2024 and 2025, CMS promulgated a series of final rules governing the marketing practices of MA Plans and their downstream third-party marketing organizations (i.e., entities compensated for performing lead generation, marketing, sales, and enrollment-related functions, otherwise known as TPMOs) (e.g., agents and brokers).[3]

On December 11, 2024, HHS-OIG issued a special fraud alert warning MA Program stakeholders about certain marketing schemes involving questionable payments and referrals between MA Plans, healthcare professionals, and TPMOs. HHS-OIG issued the alert in response to “abusive compensation arrangements” that could lead to improper steering, anticompetitive conduct, and other harms to enrollees and the Medicare program and, ultimately, criminal, civil, or administrative liability under various federal laws, including the FCA and the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS), 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b. Specifically, HHS-OIG warned against arrangements involving (i) payments by MAOs to healthcare professionals in exchange for referring patients to MA Plans and (ii) payments by healthcare professionals to TPMOs to refer Medicare beneficiaries to the healthcare professional.

In parallel, numerous recent FCA actions and associated settlements have involved the MA Program and allegedly impermissible marketing arrangements. On July 1, 2022, MCS Advantage, Inc. (MCS), an MAO, paid $4.2 million to settle allegations that MCS violated the FCA and AKS by distributing gift cards to administrative staff at healthcare provider offices to incentivize enrollment of patients in MCS’s MA Plan. More recently, on January 17, 2025, in connection with a self-disclosure, the US Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Michigan announced that Commonwealth Care Alliance, Inc. (CCA) agreed to pay more than $520,000 to resolve allegations that a company acquired by CCA violated the FCA and AKS by providing cash payments to healthcare professionals and physician practice administrative staff in exchange for patient contact information used to contact patients regarding MA Plan offerings. Accordingly, both MAOs and the healthcare professionals who contract with MAOs should be conscious of the considerable risks and potential liability associated with improper marketing arrangements and steering of patients.

With respect to SNPs, between 2023 and 2024, SNP enrollment grew by 13% (increased SNP enrollment accounted for nearly 40% of all MA Program enrollment growth over that same period).[4] MAOs have invested heavily in certain chronic condition SNPs in recent years. As of July 2024, more than 6.9 million Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in SNPs. SNPs receive higher premiums from CMS due to the acuities of patients. SNP enrollment is dependent on health conditions and medical diagnoses and codes.

Starting in plan year 2025, MA Plans must ensure that TPMO contracts do not inhibit an agent or broker’s ability to objectively assess and recommend the MA Plan that best fits the healthcare needs of a Medicare beneficiary.[5] In addition, MAOs and TPMOs must ensure that beneficiaries are informed about their MA Plan options so that they can enroll in MA Plans that best suit their health needs.[6] Accordingly, marketing arrangements associated with SNPs carry unique risks, as any marketing arrangements that arguably result in the steerage of MA Program beneficiaries to MA Plans that may not be in the best interests of such beneficiaries may expose the parties to such arrangements to FCA and AKS liability.

HHS-OIG Medicare Advantage Program Compliance Guidance

With respect to MA Program compliance generally, on November 6, 2023, HHS-OIG published its General Compliance Program Guidance (the GCPG), a voluntary, non-binding guidance document prepared by HHS-OIG to support individuals and entities participating in Federal healthcare programs in their efforts to self-monitor compliance with applicable laws and program requirements. When it released the GCPG, HHS-OIG also announced the anticipated publication of industry segment-specific compliance program guidance (ICPG) for different types of providers, suppliers, and other participants in healthcare industry subsectors or ancillary industry sectors relating to Federal health care programs. During the Biden administration, HHS-OIG indicated that it expected to publish the Medicare Advantage Program ICPG in 2025.

On March 27, 2025, HHS announced a dramatic restructuring and a downsizing of 20,000 HHS employees. It is unclear whether this downsizing (or any other Trump administrative initiative) will impact HHS-OIG’s publication of its MA Program ICPG. However, MA Program participants should continue to track the potential publication of the MA Program ICPG, as such guidance, if published, certainly may impact and inform compliance expectations in connection with future FCA actions and enforcement activity.

MA Program compliance outlook

The continued growth of the MA Program, combined with the Trump administration’s stated efforts to minimize fraud, waste, and abuse within government programs, requires MA Program stakeholders to closely monitor enforcement activity and MA Program developments. Despite the special master’s recommendation in Poehling, given the financial impact of chart reviews on MA Program costs, MA Plans should continue to expect scrutiny (both from qui tam relators and governmental agencies) of chart review processes. MAOs and providers contracting with MAOs should further ensure that their marketing arrangements—especially those involving gifts, prizes, donations, meals, etc.—are compliant to avoid potential FCA and AKS liability. Further, all individuals and entities participating in the MA Program should remain on the lookout for HHS-OIG’s MA Program ICPG and continue to be proactive with respect to MA Program compliance to minimize potential FCA exposure.

For more information on the content of this alert, please contact your Nixon Peabody attorney or the authors of this alert.

- United States ex rel. Poehling v. UnitedHealth Grp., Inc., No. CV 16-08697-FMO-PVCX, 2025 WL 682285 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 3, 2025).

[back to reference ] - See 42 CFR Part 422 Subpart V; Medicare Communications and Marketing Guidelines (Feb. 9, 2022).

[back to reference ] - See 89 Fed. Reg. 30448 (April 23, 2024).

[back to reference ] - Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, ch. 11 [The Medicare Advantage program: Status report] (March 2025).

[back to reference ] - 42 C.F.R. §422.2274(c)(13).

[back to reference ] - 42 C.F.R. §422.2274(c)(12).

[back to reference ]